The First Kettles

Joseph Rodgers McFee was a Canadian-born sailor. In 1890, after a twenty-year sailing career, Joseph sold his ship and moved with his wife, Ruth, to California. It was here that they heard a Salvation Army officer (ordained minister) preaching. His powerful words moved the McFees, and they soon became officers in The Salvation Army.

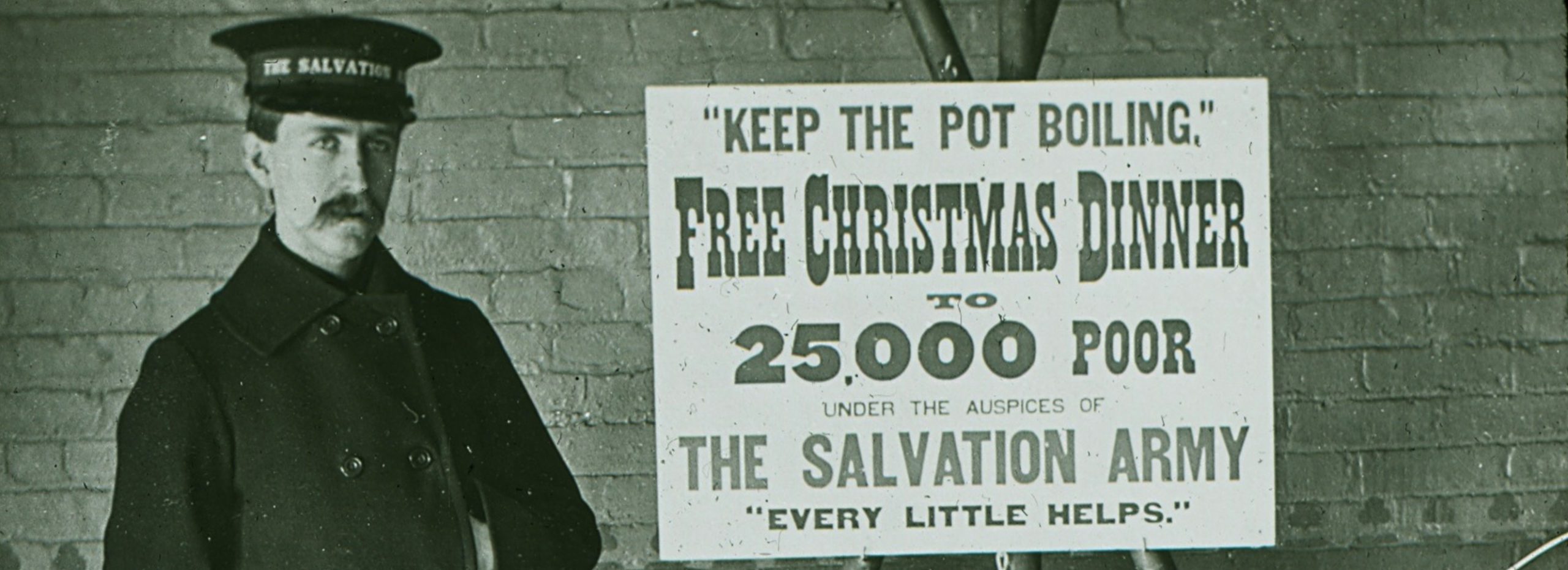

By December 1891, Joseph and Ruth McFee were serving as Salvation Army officers in San Francisco. When his corps (local church) wanted to host a Christmas Day dinner for 1,000 of San Francisco’s poor, Joseph accepted the task of raising money to pay for the meals. He then remembered the “Simpson’s pot” he saw in Liverpool, England, during his years as a sailor. The pot was a cooking kettle that a man named Simpson placed near the wharf to collect donations for the poor. Joseph decided to use this same technique and, on either December 14 or 15, 1891, he placed an iron cooking pot on San Francisco’s wharf near the ferry depot entrance. He hung a sign above the iron pot that read: ‘Fill the pot for the poor. Free dinner on Christmas Day to 1,000 poor women, children, and unemployed men.” A Salvation Army Soldier (local church member) stood guard next to the pot. A second pot, this one a brass urn, was placed in the ferry waiting room, and a third near the ferry exit. The donation pots were an immediate success.

Unfortunately, success can sometimes encourage vice. The first theft from a Salvation Army kettle occurred on December 16, 1891. The San Francisco Examiner provided details:

“The Salvation Army box at the ferries was robbed yesterday and the fund for providing Christmas dinners for the poor of San Francisco is a trifle less than four dollars out.

“The contribution box was only placed in position a day or two ago. It was an unpretentious affair, but it was big enough to hold the overflow currency of the water front.[sic] There was a piece of wire netting over the top of the box so that intending contributors could see where every nickel dropped into the slot went to.

“There were between four and five dollars in the box yesterday and a full private of the Salvation Army stood guard in close proximity to the accumulating dinner fund. There was an English shilling amongst the coins under the netting, and this was an excuse for sundry water front [sic] youngsters taking a birds-eye view of the contents in the box.

“One of the boys went a trifle further, however. He waited until the full private turned his head a moment and then plunged his little fist through the netting, clutching eagerly at the nickels and dimes and the English shilling. His clutching capacity was about $3.60, and when the private became watchful again the boy and the shortage were away in the dim distance threading lumber piles and coal yards.

“The box is still there, however, and the private more on guard than ever, while the robbery was probably a blessing in disguise, as many of those using the ferries went deep into their pockets on hearing of it and the lost sum more than replaced.”

The fundraising strategy was a success. The money from the three kettles supplemented the donations of food from local merchants. On Christmas Day 1891, using the donations of food and money, The Salvation Army hosted lunch and dinner for more than 1,100 of San Francisco’s poor at its 1135 Market Street location. The next day the San Francisco Chronicle reported on the meal:

“Quartermaster Captain McFee said that the army had purchased 800 pounds of potatoes, 450 pounds of beef, 400 pounds of fruit, 150 pounds of sugar, 100 pounds of mutton. 80 pounds of ham, 50 pounds of butter, 50 pounds of coffee, and 10 pounds of tea, besides 300 pounds of plum pudding, 150 pies and numerous cakes.”

The Pacific Coast edition of The War Cry also reported on Joseph’s great idea and the success of the Christmas Dinner. Salvation Army corps across the West learned about this new fundraising tool, and some would soon use it to help fund their Christmas dinner programs.

While the San Francisco Christmas dinner was funded in part by the first documented use of a kettle for fundraising, it was not the first time The Salvation Army hosted Christmas dinner for those in need. In the early 1890s, a handful of corps across the United States had adopted this annual tradition. The 1891 San Francisco dinner does appear to have been one of the largest to date in the United States.