Not all Kettles are Red or Round

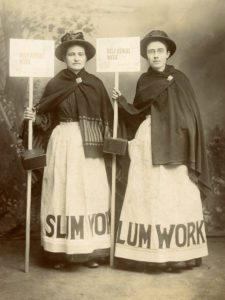

The first kettles used in the Central Territory looked a lot like the collection boxes in this photo of Chicago Slum Workers.

Under the direction of Brigadier George Sully, 1895 was the second year for the Red Kettle Campaign in Kansas City, MO. The Kansas City Times highlighted the location of more than two dozen donation boxes branded with the slogan “Every Little Helps.” The funds raised were used to host a Christmas Dinner for 1,000 people.

In 1898 Sully brought the use of donation boxes to his next appointment in Buffalo, New York. He had ten tin collection boxes made, which were staffed by Soldiers who sought donations in downtown Buffalo. Aided in the campaign by Colonel William S. Barker, their goal was to fund a Christmas dinner for 1,000.

That same year donation boxes debuted in Chicago. The Chicago Inter Ocean newspaper wrote:

“On twenty-five of the busiest down-town corners the army [sic] has stationed trusted Salvationists, who are engaged in special sentry duty with iron contribution boxes. The outfit consists of a long staff, topped by a placard containing the announcement:

“‘SALVATION ARMY — Christmas Dinner for 5,000 Poor — KINDLY HELP.’

“Below the box is fastened a small iron letter-box of the private-house pattern, and securely padlocked. The boxes readily attract the attention of the thousands of holiday shoppers who, while engaged in buying Christmas surprises for their loved ones, feel then, quite naturally, more generously and charitably disposed toward humanity in general. The boxes are reaping a generous harvest of nickels and dimes.”

These donation boxes emulated those that originated in Los Angeles in the mid-1890s. The format was used for Self Denial Week and Christmas Dinner donations by the Los Angeles, and Sacramento corps. It soon was brought to Boston, Massachusetts and other points along the East Coast and Midwest by officers from California who moved to new appointments.

In a letter from 1940, Commissioner William A. McIntyre recalled the origins of the donation box format:

“The street collecting was commenced while I was at Los Angeles by Mr. Janes Hyde. He was getting up a picture [photo collage] with the photographs of all the Army leaders throughout the world, but all the Pacific Coast friends in the best positions, and some of the top leaders back with the crowd. It was a unique idea, but he ran out of money and wanted the privilege of holding a box on the street, and the people going by put money in and it was proved to be a little river of gold. The idea of the box was afterwards used for Self-Denial and Christmas. At Frisco [San Francisco] they used the kettles – the same idea – on the street. From the coast the kettle and the box idea was taken to Boston, when I was appointed there as General Secretary, and also to New York.”

Just before Christmas 1897, Both Commissioner William McIntyre and Colonel Barker were serving in Boston. In 1940, Barker recalled how the same type of donation box was first used in Boston.

“I went up to Boston for the Christmas Holidays and Major McIntyre asked me to take over the responsibility for the Christmas dinner when the Army advertised to feed 300 men in the Army Hall. No money was available due in part to the recent changes and I conceived the idea of using the method which had once been tried out in San Francisco to raise money for Self Denial. The streets of Boston were narrow and crowded and the standard box lent themselves very well to that condition. We fed 800 men and had a considerable surplus left to help with winter relief. In Christmas of 1898 I used the same plan for Christmas in Buffalo with similar success.”

At first, the Boston Salvationists were unwilling to participate in such an unusual approach to gathering donations. McIntyre enlisted the aid of his wife and sister-in-law for the first “kettle” stands. After they received donations totaling $7 per hour, the local Salvationists warmed to the donation boxes and joined the fundraising effort.

The Boston Globe reported on the 1897 Christmas Dinner. The paper noted that almost the entire meal was financed by the street donations. It went on to say that multiple seatings of 800 persons each, totaling over 2,000 diners, attended the dinner and the leftovers were distributed to an additional 600 homes in Boston. Brigadier William J. Cozens, who was the commanding officer, declared that the diners could have as many servings as they wanted. The paper noted that some enjoyed second and third helpings. It went on to quote Cozens, “’This is the best kind of religion,’ said the Brigadier after dinner. ‘It counts for more than preaching.’”

Despite the donation boxes success, ultimately, the kettle on its tripod stand won out over the collection box as the preferred format for Christmas time street corner donations.