Professional sports are only one industry affected by the global coronavirus pandemic. Currently, hundreds of professional cyclists, coaches, and support staff are doing their best to stay healthy during the twenty-one stages of the 2020 Tour de France. Amid this added challenge, the professional peloton is pedaling 2,165 miles (3,484 km) as they transverse continental France and ride up and down five mountain ranges – quite a feat of endurance and strength, to be sure.

Professional sports are only one industry affected by the global coronavirus pandemic. Currently, hundreds of professional cyclists, coaches, and support staff are doing their best to stay healthy during the twenty-one stages of the 2020 Tour de France. Amid this added challenge, the professional peloton is pedaling 2,165 miles (3,484 km) as they transverse continental France and ride up and down five mountain ranges – quite a feat of endurance and strength, to be sure.

Following the race on television, it reminds me of another Tour de France, one that also covered thousands of miles during a global pandemic. But, this tour occurred during wartime and includes a surprise twist.

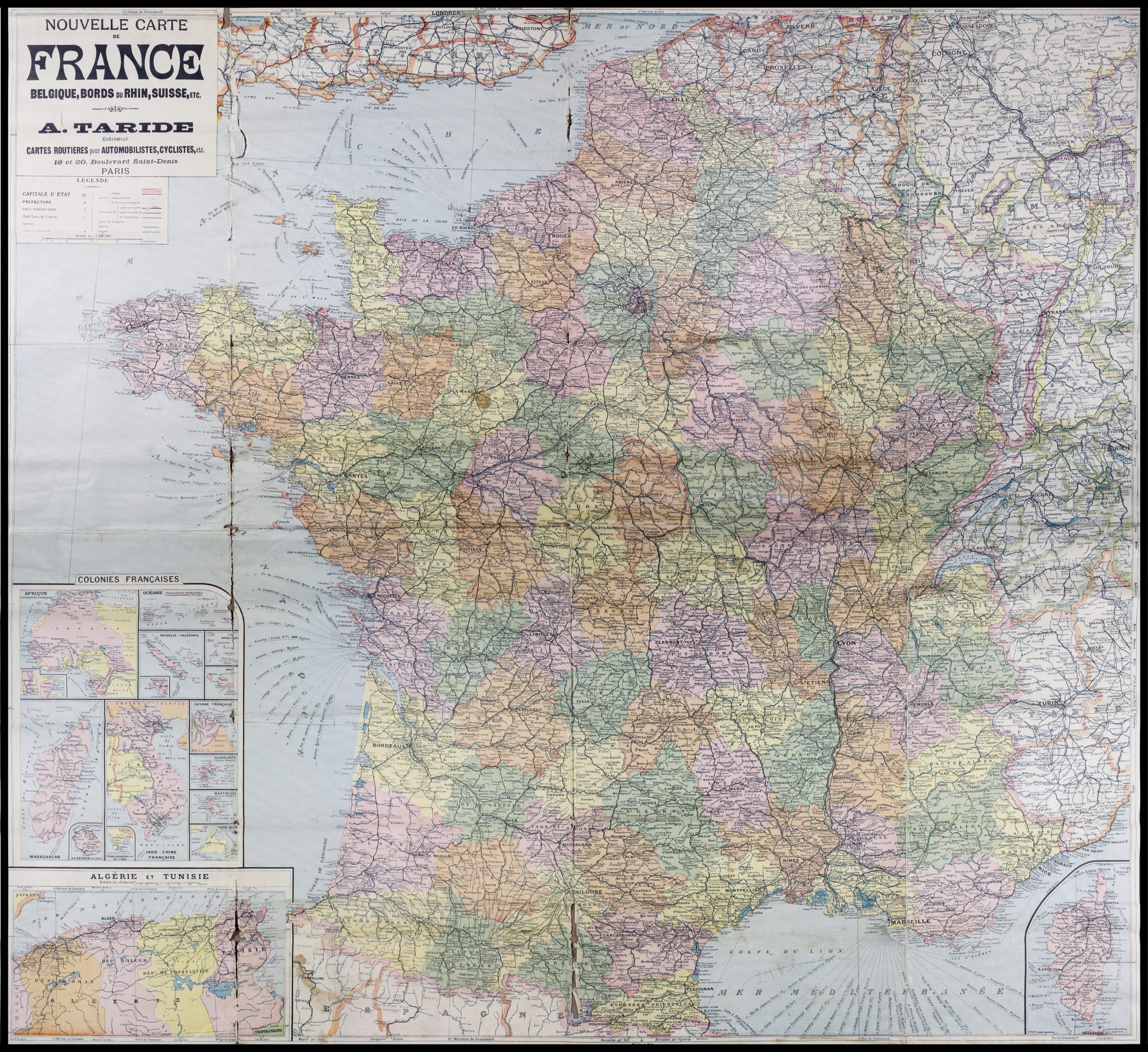

This map is one of the thousands of souvenirs acquired in France during World War I (WWI) by Doughnut Girls and doughboys alike. Souvenirs like this often serve as a memory device. They remind us of the experiences of travel and specific events.

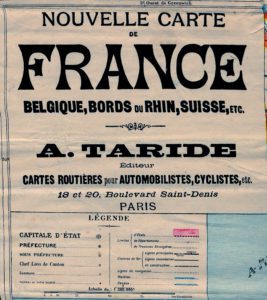

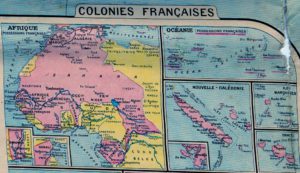

By itself, the map looks ordinary enough. The title indicates that it is an automobile and bicycling map intended to help the user to navigate their way around continental France and the French colonies. However, the legend shows that only railroads and waterways are marked. This would certainly present an interesting challenge to the motorist or cyclist. Created by the cartographic firm founded by Alfonse Taride (c. 1850-1918) and published under the name A. Taride, this map was engraved and printed by Charaire à Sceaux. There is no identifiable date, but the colonial holdings and country boundaries illustrate pre-World War I borders. This evidence dates the map to c. 1911-1916; a date range specifically based on the boarders of Alsace-Lorraine (surrendered 1919), Cameroun (acquired 1911, surrendered 1916), and Togoland (occupied 1914, formally surrendered 1916) shown on the map and identified as German lands. The absence of Syria as a French territory (acquired 1920) further defined the date range.

By itself, the map looks ordinary enough. The title indicates that it is an automobile and bicycling map intended to help the user to navigate their way around continental France and the French colonies. However, the legend shows that only railroads and waterways are marked. This would certainly present an interesting challenge to the motorist or cyclist. Created by the cartographic firm founded by Alfonse Taride (c. 1850-1918) and published under the name A. Taride, this map was engraved and printed by Charaire à Sceaux. There is no identifiable date, but the colonial holdings and country boundaries illustrate pre-World War I borders. This evidence dates the map to c. 1911-1916; a date range specifically based on the boarders of Alsace-Lorraine (surrendered 1919), Cameroun (acquired 1911, surrendered 1916), and Togoland (occupied 1914, formally surrendered 1916) shown on the map and identified as German lands. The absence of Syria as a French territory (acquired 1920) further defined the date range.

What makes the map extraordinary is the transformation by its owner into a WWI travel log. When the museum first received this map with a donation of WWI and other materials from a Burdick family descendant, it was understood that the map was owned and used by Ensigns Floyd and Minnie Burdick, who served overseas with The Salvation Army War Service. The owner of the map noted their route through France and indicated the length of stay in each location. Recently, when comparing the dates on the map to newspaper articles, it was discovered that the map did not match Floyd and Minnie’s wartime experiences. Instead, the circled landmarks and date notations pointed to the map belonging to their son, Elmer, who served in France for about ten months with the United States Signal Corps and then The Salvation Army War Service. This map serves as evidence of Elmer’s WWI journey and gives us a glimpse into how he aided his parents and sister, Lieutenant Cecil Burdick, in their Salvation Army service.

Elmer and the other members of the 6th Infantry Division, Company B, 6th Field Signal Battalion arrived at the Port of Le Havre, France on July 22, 1918. After arriving the battalion was dispatched to Chateauvillan for training. Once Elmer and his battalion were combat-ready, they were deployed to the quiet Gerdamer sector and then took part in the Muse-Argonne offensive.[i]

Elmer was discharged on February 17, 1919, at St. Aignan, possibly in response to his sister and parents recovering from illness while serving with The Salvation Army War Service. Cecil contracted the Spanish Flu while on furlough in Niece in January 1919, and Floyd may have also fallen ill with the virus. He reported being ill for two months and too weak to help his wife, Minnie, in their hut.[ii] The exact dates when Minnie suffered exhaustion and was hospitalized in Paris are unknown, but she may also have been recovering during this same period. After his discharge from the US Army, Elmer traveled north to Paris, where he joined his parents and sister. Here he was fitted for a Salvation Army War Service uniform and proceeded with his parents to the large US military base at Brest. Floyd noted the hut, located in a large airplane hangar, could seat 2,000 soldiers. Here soldiers enjoyed their fill of freshly fried doughnuts and listened to the Burdicks preach the Gospel before returning to the United States.[iii]

On April 22, 1919, Elmer’s Tour de France ended. He and his parents set sail on the S.S. New Amsterdam for New York. Cecil remained in France and Germany for several months serving the troops. Elmer returned to his wife and two children in Houston, Texas. There he resumed his pre-war job as a postal carrier.

Elmer’s Tour de France as noted on map

| Le Havre | July 22, 1918 |

| Chateauvillan | July 25 – September 1, 1918 |

| Geradremer | September 1 – November 1, 1918 |

| Sainte Menehould | November 1, 1918 |

| Stenay | November 6 – 9, 1918 |

| Montfaucon | November 11, 1918 |

| Verdun | November 14 – 22, 1918 |

| Quemigny | December 6, 1918 – February 1, 1919 |

| St. Aignan (discharged) | February 17, 1919 |

| Paris | February 19 – 25, 1919 |

| Brest | February 25 – April 22, 1919 |

Map and photos Gift of Pamela Feack in memory of Floyd O. “Pa” and Samantha Minerva “Minnie, Ma” Saunders Burdick, Cecil May Burdick Goodwin, Grace Belle Burdick Yates, and Fern Ann Goodwin Feack

[i] Accessed from https://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwi/fieldoperations/CombatDivs.html on 9/2/2020.

[ii] “World Famous Burdicks, Salvation Army Workers, Are Home from France.” By Paul M. Sarazan Unidentified newspaper, clipping located in scrapbook, Salvation Army Central Territory Museum collection.

[iii] “World Famous Burdicks…”